Cool. n.

Enhances human powers with a natural ease, never needing to shout.

Balances power and humility, combining confidence with subtle restraint.

Empathetic and adaptable, embodying an understated strength.

Unforced and effective, steering clear of the over-engineered or desperate.

Quietly makes us better, working in the background like the best kind of technology.

For centuries, technology has evolved to extend human reach and enhance our autonomy. From the invention of the printing press to the steam engine, the story of innovation was about opening up new horizons and giving individuals the power to explore, create, and connect. The age of machines brought us looms and steam engines. We got the bicycle, for instance—a moment akin to walking on the moon (or not). With more than a billion in circulation today, it’s a straightforward yet transformative tool that doesn’t require updates, subscriptions, or data tracking. It’s just you, the wheels, and the open road—a reminder that technology can be liberating without strings attached. Bikes are cool. (They’re not. But we persist in this illusion.)

Today, however, Silicon Valley’s version of “cool” seems to revel in subverting these ideals. Much of contemporary technology subtly erodes personal autonomy, entwining users within ecosystems that demand continual updates, surveillance, and an unrelenting connection to the cloud. Once, the tech industry’s vision heralded promises of liberation and expanded choice, but now it’s more reminiscent of a digital hamster wheel, where escape is a quaint illusion, and most roads lead to server farms in the desert. These are not the tools of empowerment, but rather complex architectures of control that transfer power to a handful of large corporations, all while suggesting we should feel grateful.

Historical contexts serve as a reminder that not all technological advances are as freedom-enhancing as advertised. The machine gun, a grim tool of mechanized warfare, claimed countless lives with ruthless efficiency, while the guillotine cut to the chase, epitomizing an efficient use of technology for political repression. Neither device bothered with the pretense of delivering freedom—both were blunt, unambiguous, and effective. By contrast, contemporary technologies often don the disguise of empowerment, yet quietly cultivate dependencies that chip away at personal agency. Beneath the glossy rhetoric of “enhancing experience,” today’s digital tools often align more closely with the interests of centralized power than with those of individual users, presenting a cunning challenge to the values of autonomy and freedom that once inspired technological progress.

I’m here to change all that.

The Most Uncool Technologies of All Time

Technology ; Reason for Uncool Status

Electric Chair

Gruesome and ominous, adding a dark twist to the concept of “taking a seat.”

Clippy (Microsoft)

The intrusive paperclip that made Microsoft Word feel like a nagging relative.

The Segway

Transport of the future…for mall cops. Nearly cool, but just not quite.

Pop-Up Ads

Like digital gnats, swarming in just when you’re reading something important.

Autotune

Draining the soul out of music, one robotically corrected note at a time.

Above-Ground Pools

The “luxury” pool that lets you swim right next to your garden gnome.

Mankinis

An assault on public decency. The less said, the better.

Robocalls

Modern tele-nuisance that has you picking up the phone just to be offered fake warranties.

Facebook’s “Poke”

The awkward way to say “hello” online that nobody knew how to respond to.

Shake Weight

Fitness equipment or accidental innuendo? You decide.

Google Glass

A cyborg dream that proved to be more about public embarrassment than cool gadgetry.

Email Spam

Overflowing inboxes with junk that almost everyone promptly deletes.

Fanny Packs

Once relegated to tourists and dads, now they’re back—but are they really cool? Hard to say.

Man Buns

Some find it stylish; others think it’s an unnecessary accessory to casual brooding.

A Brief Stuffy History of Cool

It is plausible that the notion of "coolness" emerged during humanity's earliest artistic endeavors, those primordial acts of creative expression that predate civilization itself. Picture, if you will, a Neanderthal gazing at his handiwork on a cave wall, perhaps smirking with a rare sense of satisfaction as he dabbed red and black ochre onto rough stone. Such an act, fundamentally purposeless and profoundly human, might well mark the genesis of cool.

By the time we arrive at the era of the pyramids, coolness had ascended to divine realms. In ancient Egypt, pharaohs embodied an untouchable cool—grandeur and mystery incarnate, commanding both reverence and fear. To achieve eternal coolness, one had to be interred with treasures vast enough to astonish the gods. The cool factor, it appears, was directly proportional to one’s amassed wealth and status in the afterlife.

Turning to the biblical tale of Moses, we find an intriguing moment of unadorned practicality. He famously parted the Red Sea using nothing but a staff—a crude instrument, perhaps, yet imbued with immense symbolic potency. The staff itself may lack the dazzle of later technological advancements, but there is an undeniable coolness in its sheer efficacy. Moses’ deed encapsulates a profound truth: coolness often lies in the simplicity of getting the job done. Thy rod and thy staff comforted Moses. (They didn’t.)

The Greeks, however, truly institutionalized cool. Their cultural contributions—democracy, philosophy, and the Olympic Games—form a harmonious blend of physical prowess, intellectual rigor, and aesthetic beauty. Coolness, for the Greeks, was an art, a state of balance. The Romans, conversely, commercialized and perhaps even corrupted cool. They embraced gladiatorial spectacle and bacchanalian excess to such an extent that they nearly turned cool into a grotesque parody of itself. For the Romans, cool became a commodity, something that could be exploited, even degraded, until—quite literally—lions entered the arena.

By the Industrial Revolution, machines redefined cool. The steam engine and the locomotive opened new horizons, enabling humans to transcend the limits of muscle and sinew. This was an age when Manchester’s soot-laden air concealed a profound transformation: progress. Nietzsche famously posited that what is good is that which increases power, and here, power was indeed cool (power is, here, polysemic). Beakers and Bunsen burners, once the tools of alchemists, were now wielded by chemists and engineers to harness actual physical reactions, harnessing a long-awaited Promethean fire.

And so, we arrive in the modern era, where the coolness of technology emancipates and feels creepy like a prison warden. Technology is no longer simply a tool; it has become a lens through which we interpret the world. Hospitals, perhaps, may not exude cool in the traditional sense, yet the act of emerging healed from one is undeniably so. Coolness, then, is not merely a function of innovation or advancement; it is an ineffable quality that, like groove, one must feel rather than define. You either have it, or you are left counting steps on a metaphorical dance floor, forever chasing … that …elusive … beat.

When You’re Keeping it Too Cool

Modern technology often arrives wrapped in the mantle of “cool,” yet much of it operates at odds with the very ideals it purports to uphold. Consider the case of Large Language Models (LLMs). While they demonstrate impressive computational prowess, their very existence hinges on the consumption of massive server resources and the aggregation of vast quantities of data. In this sense, they are less the nimble tools of personal empowerment and more the sprawling edifices of a heavily centralized, infrastructural empire. Sure, we’re not being used as batteries yet, but we’re oddly and troublingly off the cry freedom path, for sure. (We are.)

The allure of AI and cognate technologies lies in the promise of simplification, yet they subtly bind users to ecosystems that operate under an unspoken code of surveillance and continual update. The latest AI-powered platforms, for instance, promise a frictionless user experience while quietly collecting and monetizing our digital footprints. Far from extending freedom, they extend the reach of those who manage the underlying networks, casting users as both consumers and data sources.

Then there is the matter of digital connection. Social media, ostensibly designed to bridge divides and foster community, often becomes a breeding ground for tribalism and echo chambers. These platforms subtly erode personal agency, encouraging conformity and engineered outrage. In a twist of irony, today’s “cool” tech has become a carefully engineered scaffold of dependency, a shiny surface concealing a more rigid structure of control.

Some Jingoistic Stuff that’s Kinda True

Back in the day, we dreamed big. Flying cars, Rosie the Robot, jetpacks. The late David Graeber once remarked that he felt a profound sense of disappointment, as if he’d been let down, growing up in the 1960s and imbibing that heady punch of Star Wars space ships and light sabers and… flying cars. Now, our biggest innovations come in the form of new ways to subscribe. Public libraries gave us open access to knowledge, but now we have streaming paywalls and closed networks. Tocqueville got it right when he said, “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.” We used to build with purpose. Now we just upgrade with profit in mind.

Cool / Not Cool: The Definitive List

Cool Not Cool

Printing Press — Automatic Faucets

Community Chat Rooms (BBS) — Social Media

Personal Computers — Phones You Can’t Repair

Public Libraries — Streaming Paywalls

3D Printers — Smart Fridges

GPS-free Adventures — GPS-dependency

Rosie the Robot — Roomba with a Subscription

The Oxford Comma — Texts Ending with "af" from Gen Z

The Cool Principle: Tech That Empowers ‘Yo Ass’

Cool tech isn’t about complexity for complexity’s sake. It’s about letting you define the experience. Larry Page once said, “Technology should be about amplifying human potential.” Real cool tech? It makes your life richer, not just more efficient. It puts you in the driver’s seat, not the passenger seat of some self-driving corporate agenda.

“Our guiding principle is that the forms of order that emerge are the result of human action, but not of human design.” – Michael Polanyi

The best tools don’t assume they know what you want. They let you carve your own path. They amplify your potential without caging your curiosity. The best tools make you cooler if you’re already cool, and put you in the running if you’re not. Digital tech is the triumph of not just the geekiness of Silicon Valley, which can be a remarkably gee-wiz and even cool place, but of control, which is never cool.

I have an erstwhile friend (somewhat of a friend) who is Ukrainian and now lives in Mother Russia. He was fond of bragging about Russia and about Putin bare chested horse riding the Slavs into the future, until I pointed out that Putin was one of the richest people in the world and, well, it’s not cool to let some prick steal your money and replace it with crappy speeches appealing to the destiny of the Russian people when the borsht is too many dengi (I think that’s money) because the dude with six yachts is taking yet more. (So, you get all the ladies and all the cash, and we get “destiny”? I think I’ll take the babes and dinero, thanks much.) Want to see how cool you are in Russia? Go protest for an afternoon. Cell Block 5, or 6? Where’d you go, broheme?

But I digress.

The James Bond Effect: Less is More, and That’s Cool

James Bond’s gadgets? Sleek, subtle, deadly efficient. The most high-tech they get is a laser watch, maybe a tricked-out Aston Martin. Bond doesn’t need a smart home device that’s spying on him or a fridge that reminds him he’s out of kale. He needs things that work, that let him be free, and that don’t ask him to accept Terms and Conditions just to use the ejector seat.

And let’s be honest, Bond wouldn’t have time for updates. Imagine if he was in the middle of a mission and his watch needed a reboot. That’s what cool tech is about—it just works. You don’t have to think about it. You don’t need a tutorial or a customer support hotline. And you don’t need an apology email from the CEO when it all goes sideways.

Moneypenny. Blasts off surreptitiously to a hotel in Macao to Bond’s surprise and delight. Moneypenny shaves Bond with a cutthroat razor, and says, "Sometimes the old ways are the best." The Bond movies—thanks to their creator, the chain smoking hard drinking Ian Fleming in the house!—are replete with cautionary quips about letting technology takeover and make you uncool. I’m being serious here. I’ll prove it. In the 1960s hit From Russia with Love, Bond makes the point lighting a smoke:

BOND Oh, fine. (reaches into his coat and takes out a cigarette case)

Can I borrow a match?

CHAUFFEUR I use a lighter.

BOND (opening the case to reveal cigarettes) It's better still.

CHAUFFEUR Until they go wrong.

BOND (shutting the case) Exactly.

Until they go wrong. That’s a major piece of the puzzle about modern tech and the phenomenon of loss of cool. Global loss of cool.

Bond is basically a masterclass on how not to become uncool in a world of AI. In Specter he delivers one of his favorite ideas to Moneypenny, again:

Bond: I heard a name in Mexico: the Pale King.

Moneypenny: You want me to be your mole.

Bond: Yes.

Moneypenny: And what makes you think you can trust me?

Bond: Instinct.

Instinct is what technophiles and futurists would like to do away with. Instinct suggests we don’t need big data to solve the various conundrums and mysteries of life, and if it suggests big data AI isn’t sufficient, it positively screams from the rooftop that instinct is necessary for cool. Want to be cool? Next time someone asks you how you know or do something—anything at all—just say “instinct.” Drop the mic.

Matt Crawford is cool. He says stuff like this (I paraphrase):

Our tools are what ground us in the real world. Without them, we are unmoored, dependent, and vulnerable.”1

Continue.

A Brief History of Cool, Redux.

Cool wasn’t always a commodity, and it certainly wasn’t always for sale. The roots of cool trace back to jazz in the 1940s, when "cool" was an attitude—a response to the world, a way to exist at the edges of mainstream culture. Icons like Miles Davis and Billie Holiday didn’t just play music; they embodied a certain resistance to conformity, a depth that couldn’t be manufactured. Coolness was complex, a blend of authenticity, creativity, and defiance.

Fast forward to the 1960s, and cool had migrated into the counterculture. The Beat Generation poets and rock stars like Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix redefined cool as an anti-establishment force. To be cool was to stand apart from the corporate machine, to reject the status quo. It wasn’t about selling an image; it was about living a life that challenged norms.

Then came the 1980s and 90s, an era when cool began to be commodified. Nike sneakers and Levi’s jeans became symbols of identity and rebellion, cleverly packaged by brands and sold back to consumers. The rise of advertising meant that cool could be crafted, curated, and bought, marking a shift from culture to consumerism.

Enter Silicon Valley. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, tech startups promised a new kind of cool—a blend of intellectual audacity and disruption. Icons like Steve Jobs, Sergey Brin, and Mark Zuckerberg were the new rebels, seemingly rewriting the rules and breaking free from corporate conformity. Cool was no longer about jazz clubs or smoky dive bars; it was in boardrooms, on the web, and soon enough, in our pockets.

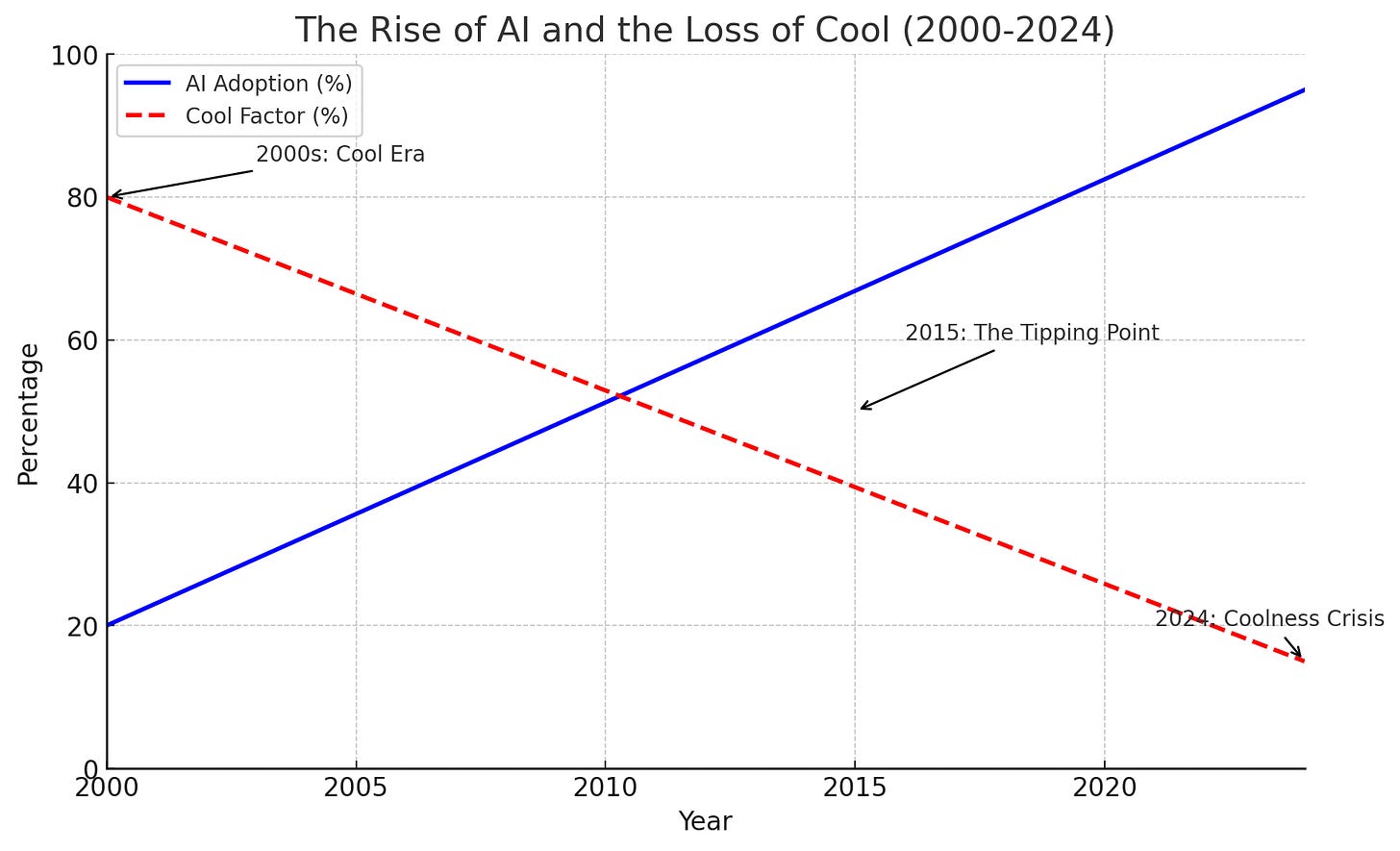

But as the tech industry boomed, it started looking less like a rebellious upstart and more like the corporate behemoths it once defied. Facebook and Google became surveillance machines; Uber was beset by scandal. The cool factor faded, replaced by a sterile, data-driven culture obsessed with optimization over originality. Cool became a casualty of progress, and Silicon Valley, once the poster child of innovation, became synonymous with something decidedly less chic: power and profit over people.

This shift didn’t just alter the face of cool; it challenged the very foundation of human agency. Philosophers Michael Polanyi and more recently thinkers like Nick Carr and Jaron Lanier have long argued that human freedom is rooted in a direct, personal engagement with the world. Crawford, too, sees this autonomy as an embodied experience—our ability to act in and on the world without interference. He warns against technologies that mediate our actions, reducing us to passive recipients of information. This is where Silicon Valley’s transformation has had a profound impact: by centralizing control and relying on data extraction, it has slowly encroached on the individual's capacity to act freely and authentically.

Michael Polanyi adds another dimension to this critique. In his view, genuine knowledge is personal and experiential, grounded in tacit understanding. He argues that when knowledge is reduced to data points or algorithms, it loses its connection to human experience. Silicon Valley’s model of centralizing knowledge through data has done just that—stripping knowledge of its personal context and reducing it to patterns in a database. In the process, it undermines the autonomy that comes from a direct relationship with the world.

The result is a tech ecosystem that trades on surveillance and commodifies every interaction. The tech giants that once promised to connect and empower us have become gatekeepers of our choices, filtering what we see, hear, and even feel through a lens calibrated for profit. This centralized control over information flows means that our sense of autonomy is subtly eroded. Instead of navigating the world on our terms, we’re channeled through paths predetermined by algorithms designed to capture our attention and, ultimately, our selves.

So, while Silicon Valley was once synonymous with cool rebellion, it has now come to represent a kind of digital enclosure, where the freedom to act and think independently is increasingly constrained by systems that prioritize efficiency over individuality. The tech that promised to set us free has instead narrowed our range of action, turning cool into something we consume rather than something we create. That’s why I’m calling on everyone to help me make the Superfly.

Superfly: The Fruit Fly-Inspired Level 5 Autonomous Vehicle

Imagine a car that doesn’t rely on a behemoth LLM or a million-dollar server farm. Instead, it navigates like a fruit fly—light, agile, instinctive. Reverse-engineer the fly's connectome, map out its hyper-efficient neural pathways, and suddenly you have a machine that moves with the elegance and precision of nature itself. Call it Superfly.

No need for endless data streams or satellite networks here. Superfly operates on the bare essentials: 140,000 neurons and about 55 million connections, meticulously mapped and fine-tuned. These compact neural circuits are all it takes to avoid obstacles, find optimal routes, and even make split-second evasive maneuvers. Superfly leverages evolutionary design, embracing a nervous system honed by millions of years of natural selection. It doesn’t rely on external servers or vast databases, but on what can only be described as the wisdom of fruit fly ancestors.

That’s innovation with soul. Superfly embodies tech that isn’t just functional—it’s a conversation piece, an emblem of what happens when we look to nature’s efficiency rather than brute computational force to solve complex problems. Its design is minimal but effective, proving that you don’t need server farms when you have a neural architecture built for agility and survival.

Superfly. A car that doesn’t just drive but glides, soars, and swoops like something alive. It maneuvers through traffic with the finesse of a fly dodging a swatter, all while retaining an elegance that only nature’s design could inspire. Now that’s cool.

Continue.

Mr. Incredible vs. IncrediBoy: The Battle for Authentic Cool

Let’s talk about Mr. Incredible and IncrediBoy. In the 2000s hit The Incredibles, we find a perfect parable for our current techno-cultural predicament. You see, everywhere in our culture, we hear cautionary voices about the creep of technology, and in particular, our latest dystopian dip into mega-data-machines billed as “intelligence.” It’s dangerous. But we already have the resources to recover cool. And few illustrate this better than Mr. Incredible and his would-be protégé, IncrediBoy.

IncrediBoy is the quintessential product of technological compensation. Lacking innate superpowers, he manufactures an entire armamentarium of gadgets and devices to mimic abilities he does not organically possess. His dependency on exogenous machinery represents a persistent desire to overcome natural deficits through artificial augmentation. Indeed, IncrediBoy is the avatar of a culture obsessed with using technology to paper over gaps in natural talent. This, unfortunately, is decidedly not cool.

Mr. Incredible, on the other hand, is the apotheosis of unadulterated natural endowment. Despite his corpulence—what might generously be described as a formidable mass—he embodies raw, unprocessed power. His prowess is not a result of engineered algorithms or synthetic enhancements; rather, it emanates from a primal authenticity. In the realm of cool, Mr. Incredible is an exemplar of a long-forgotten ideal: a return to form, an embrace of inherent capabilities over manufactured substitutes. His strength lies not just in his physical abilities but in his self-reliance, his unyielding confidence in his own, biologically rooted gifts.

The IncrediBoy phenomenon illustrates a broader societal trend: the increasing inclination to substitute natural aptitudes with technological artifacts, often under the guise of progress. But Mr. Incredible reminds us that coolness, true coolness, is deeply intertwined with authenticity. It’s not about hacking one’s limitations; it’s about embracing and optimizing one’s inherent traits. Herein lies the cautionary message of The Incredibles: the further we drift from our intrinsic capacities in pursuit of artificially derived powers, the further we stray from the essence of cool.

Why AI is Uncool Today

AI and big data, by their very nature, undermine the essence of cool by necessitating a kind of cultural expropriation. For these technologies to function, they must ingest vast quantities of data—data that constitutes the sum of human experience, creativity, and identity. This is not merely a transaction; it is a subsumption of human culture into an algorithmic framework, one that is then restructured, repackaged, and resold by entities that retain exclusive ownership over the intellectual territory they harvest.

Admittedly, the allure of these systems lies in their utilitarian advantages. Large Language Models, for instance, would have little appeal were it not for their capacity to deliver efficiencies and solutions that resonate on a practical level. However, it would be naïve to view these conveniences as a fair exchange. The data requisites and astonishing energy demands of these “Monster Truck AIs” represent only half of the dilemma. The remaining half is more insidious: these technologies are centrally administered, under the control of a limited number of private entities, thereby exacerbating existing socio-economic disparities.

Such technologies don’t simply consume resources—they centralize power, consolidating it within the upper echelons of a narrow tech elite. In doing so, they erode the middle ground, creating a bifurcated landscape that prioritizes profit over plurality. The systems ostensibly augment our agency by furnishing us with tools of unprecedented utility. Yet, they simultaneously strip away the very control they promise, embedding us ever more deeply into ecosystems that, though accessible, are neither owned nor directed by us.

And herein lies the ultimate betrayal of cool: a relinquishment of autonomy disguised as enhancement. Throughout history, centralized systems have consistently veiled their true intent—expanding control and cultivating dependency, all while maintaining an illusory sense of individual empowerment. What begins as a symbiotic relationship frequently morphs into a scenario of imposed fealty, where our roles as users subtly transform into those of subordinates within a digital dominion.

This trajectory, once understood, reveals an uncomfortable truth. We are relinquishing more than we gain in return. By surrendering the decentralization of culture, we are sacrificing the unmediated autonomy that cool demands, exchanging it for a superficial extension of reach. The tools, while potent, do not liberate us; they ensnare us, diminishing our influence while amplifying that of a select few.

Empirical data supports this trajectory. Wealth consolidation among AI stakeholders is pronounced, with a small fraction of the population capturing the lion’s share of generated value. Energy demands for AI infrastructures are projected to rival that of entire nations, underscoring an unsustainable model. The notion that this technology might foster greater individual empowerment is, at best, illusory. The statistical evidence paints a stark picture: the system is engineered to favor those at the apex, leaving the broader public to grapple with the vestiges of control once thought secure.

Ultimately, the architecture of this exchange is unmistakably asymmetrical. Cool was never about relinquishing control; it was, and remains, about embodying an authentic autonomy. Any system that demands this forfeiture in exchange for a fleeting semblance of power diverges fundamentally from the principles of cool. In this light, AI and big data are not merely uncool—they are the antithesis of what cool aspires to be.

Superfly, Redux

Superfly, Redux: A Paradigm Shift with the Fly Connectome and Liquid Neural Networks

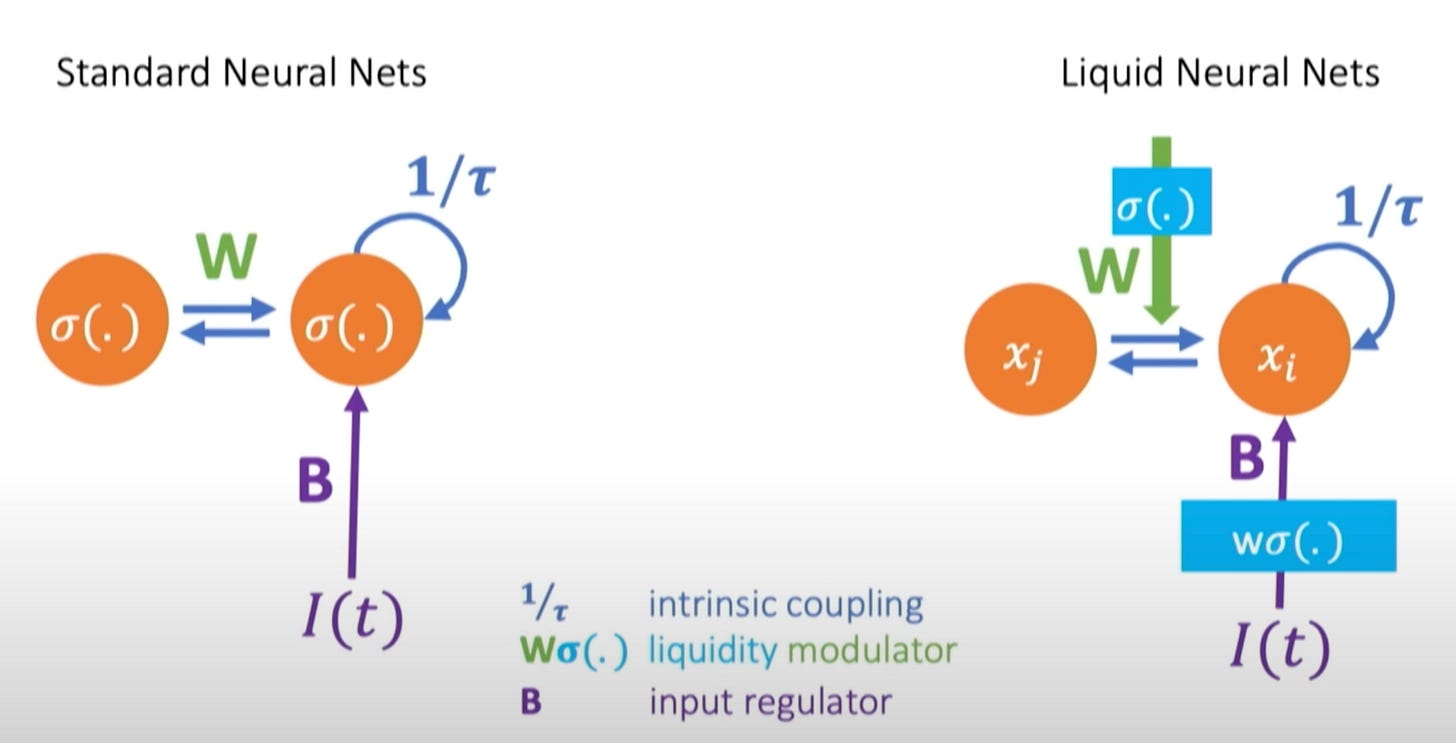

Superfly’s innovation lies not merely in imaginative design but in the rigorous application of scientific principles derived from nature. Diverging from the data-heavy AI frameworks of OpenAI, Google, and Meta, Superfly bases its intelligence on the fly connectome, which researchers have now successfully mapped—a sophisticated neural structure comprising approximately 140,000 neurons and 55 million synaptic connections. By emulating this biological model, Superfly circumvents the need for vast data sets and instead adopts a streamlined approach, leveraging the optimized efficiency inherent to natural systems.

Yet the distinctiveness of Superfly’s architecture is not confined to its biological inspiration. This model integrates MIT’s Liquid Neural Networks, an emergent technology noted for its capacity to facilitate continuous, real-time adaptation. Unlike traditional AI systems, which demand extensive retraining with immense data reserves, Liquid Neural Networks enable Superfly to adjust fluidly to new stimuli and conditions as they arise. The adaptability of this neural architecture allows Superfly to maintain a responsive intelligence that is both flexible and scalable, traits that are especially advantageous in dynamic environments.

By synthesizing insights from the fly connectome with the advanced learning capabilities of Liquid Neural Networks, Superfly embodies a novel AI paradigm. This approach eschews the data-intensive tendencies of conventional systems, opting instead for a leaner, more organic mode of operation. Superfly thus exemplifies a divergence from the prevailing model of AI as a lumbering entity of massive computational power and pervasive data acquisition. Rather, it offers a vision of AI as responsive and resource-efficient, rooted in the elegance of natural biological frameworks.

Superfly’s distinct appeal, therefore, lies not only in its technological prowess but in the shift it represents toward an AI that is less intrusive, more adaptive, and ultimately more aligned with the principles of natural intelligence. In an era dominated by centralized, data-intensive AI behemoths, Superfly’s approach marks a compelling departure toward a model that is as intellectually rigorous as it is practically efficient.

Artist’s Rendering of Superfly

Coolness versus Grooving: An Examination of Aesthetic Modalities

In the discourse of contemporary aesthetics, one finds it imperative to delineate between “coolness” and its lesser-discussed cousin, “grooving.” Though the terms may appear synonymous, a closer inspection reveals fundamental distinctions that speak to the underlying nature of each. Coolness, as previously established, embodies a detachment and an aura of effortless autonomy. It is characterized by a state of unflappable composure, where one remains impervious to external influence—a quality admired and, indeed, revered.

Grooving, on the other hand, invites a more participatory engagement with the rhythms of one’s environment. To groove is not merely to be; it is to move, to attune oneself to an external beat, often with a head-bobbing vigor that borders on ebullience. While coolness might walk into a room and assess the scene with an aloof detachment, grooving would saunter in, immediately swaying to the tempo, perhaps even nodding at strangers with a knowing grin. Coolness transcends; grooving is down-to-earth.

This difference is not without its implications. To be cool is to remain distinctly unperturbed, exuding an air of mastery over one’s surroundings. A cool individual might sip their beverage in contemplative silence, projecting an aura of mystery. Conversely, to groove is to lose oneself in the communal spirit—an activity that, while undeniably joyous, involves an inherent surrender. The groover aligns with the beat, sacrificing the stoic sovereignty of coolness for a more animated participation.

Consider a real-world example: an individual at a jazz club, tapping their foot while nodding appreciatively yet impassively at the musicians on stage—this is coolness personified. Meanwhile, the person a few seats over, fully engrossed, snapping fingers and bobbing their head with exuberant abandon? They are grooving. Both positions hold aesthetic merit, yet only one retains the detached elegance that has become synonymous with true cool.

In considering these aesthetic modalities, one must ask: is it better to groove with the crowd or to stand apart, unmoved by the pull of popular rhythms? Is it nobler to suffer the slings and arrows of an anxious and venomous cancel culture, or to take arms against the sea of troubles, and by opposing, end them?2 The answer, of course, hinges on one’s priorities. Grooving invites a communal alignment, a synchrony with the external flow, while coolness champions autonomy—a refusal to be absorbed by fleeting trends. In an age where the masses are increasingly guided by algorithmic determinism, the revival of coolness signals a reassertion of individuality. Coolness resists the calculated and the controlled, embracing an independence that feels both timely and timeless.

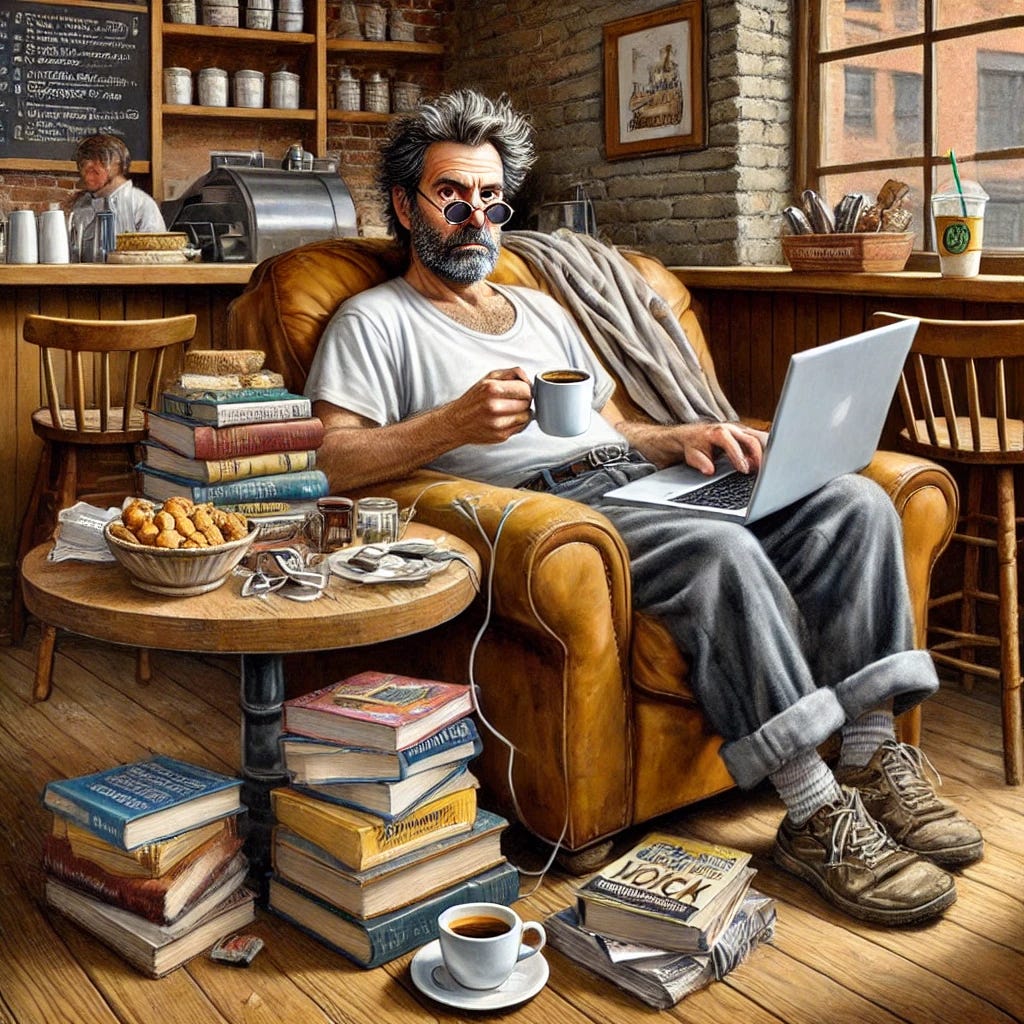

Thus, as the cool cat may sip his coffee with a detached elegance, contemplating the subtleties of an old vinyl record, the groover no doubt taps along, fully immersed in the kinetic embrace of the vibe. Each embodies a distinct approach to existence: the cool cat, untouched by external cadence, exemplifies the allure of self-possession, while the groover, exuberantly enmeshed in the moment, finds fulfillment in a shared experience. In the final analysis, the decision between coolness and grooving is less a matter of superiority and more a reflection of where one finds solace—either in the quietude of autonomy or in the kinetic embrace of the vibe.

Coolness vs. Grooving

Reclaiming Cool: Pathways to Restoring Autonomy in the Age of AI

The restoration of cool in our technologically mediated world necessitates a return to principles that favor human autonomy and agency over corporate hegemony and algorithmic imposition. In the wake of a digital era that has largely privileged centralized systems, a recalibration is required—one that can reintroduce individuality, self-determination, and, indeed, coolness into our daily lives. The question, therefore, is not whether such a restoration is possible, but rather how it can be achieved within the practical constraints of our contemporary world.

One illustrative avenue for this restoration is through the resurgence of localized, community-centric digital infrastructures. Take, for example, the neighborhood mesh network. Imagine having your own hyper-local internet that doesn’t extend beyond a few streets, but includes everyone on your block and maybe that guy in the coffee shop who never leaves. It’s the modern equivalent of the town square—but with a Wi-Fi password. By adopting such decentralized technologies, individuals cultivate digital ecosystems that prioritize direct engagement over opaque intermediation. No more reliance on data-harvesting behemoths; instead, you control your own digital domain, complete with local gossip and occasional cat memes.

To reclaim coolness, we need to fundamentally reconsider how we manage personal data, embracing a deliberate, restrained online presence. Rather than scattering digital traces across countless platforms like confetti at a party we didn’t want to attend, the essence of coolness today might lie in selective, almost artful participation. Imagine logging into just one social media platform, posting a single, carefully-curated photo, then vanishing like a digital ghost. Algorithms may try to track you, but you’ve left them grasping at shadows. This is data minimalism at its finest—a quiet rebellion against oversharing, where every post is a statement and every absence is a mystery. Your profile becomes less of a window and more of a peephole, preserving your autonomy and subtly declaring, “I’ll decide how much of my soul you get to see.”

On a similar note, reclaiming cool also means aligning with services that prioritize user empowerment over corporate profit margins. Consider Bitcoin and other decentralized finance platforms: they offer the chance to escape traditional banking’s clutches, an act of digital liberation that might just make you the crypto-revolutionary your high school self always dreamed of. Sure, you may well end up in a white-collar prison alongside Sam Bankman-Fried, swapping stories about misplaced billions. And yes, you might find yourself inexplicably linked to Russian billionaires on various wanted lists. But you’re crypto now—liberated from traditional chains, free to navigate the financial wild west with nothing but encrypted passwords and a disregard for conventional banking systems.

Slash Solo in Sweet Child O’ Mine

Finally, reclaiming coolness in this era might entail embracing analog experiences that inherently resist digitization. After all, nothing says autonomy like sending a handwritten letter—an act that not only confounds the recipient but also your mail carrier, who’s genuinely unsure if it’s still 2024. By engaging in these decidedly non-digital practices, one asserts a form of autonomy that AI simply cannot replicate. It’s the kind of radical cool that no algorithm can anticipate. Analog stands in proud defiance of digital conformity.

In sum, the path to reclaiming cool in a world overrun by surveillance and data exploitation is one that encourages the conscious, deliberate reassertion of human autonomy. Through local networks, selective data sharing, ethically aligned consumer choices, and analog engagements, we can steer toward a future that values individuality over algorithmic assimilation. The measures don’t just promise a restoration of cool; they offer a subtle reminder that some things—like sending a postcard—are simply beyond the grasp of AI.

Artist’s Rendering of the Guy Who Never Leaves

You’re Taking Cool Back? Sheeot, that’s all you had to say!

I said I was bringing cool back, but I can't. We can. Pro tip: futurists insist that humans are on their way out the door, and that machines are the next era. What a cruel joke, as the reality is we're living in an impoverished era of technophiles and technocrats who increasingly believe, it would seem, their own blather. We're humans, dammit. We play music. We write. We sing. We forget to take the trash out. We dream. We break into spontaneous laughter, we dance badly, and we cook meals that don’t always turn out right.

We're taking cool back. We're grooving. We're still cool. And we’re just getting started.

I was looking for a quote from

and didn’t find the one I wanted. So, this is a paraphrase and I trust unobjectionable.Here I am just talking shit.

Damn you've been busy today! I feel proud to have poked the bear. Seriously, this is really good, in a stream of brilliant consciousness sort of way. Thank you. This is, to use a word I don't like, progress. Onward.

Huh. You have made a very good argument that I am cool. I'll take it.

Re: the big LLMs and their fiefdoms, this is why I insist on my little LLM project being able to run on consumer hardware or bust.

I like the idea of Superfly. But mapping a fruit fly's connectome and understanding how it *works* are two different things. In over to transfer it to a car it will have to be reverse engineered and reworked. I still have strong doubts that the simulated synapse model is the complete picture. The mapped connectome may turn out to be about as useful as the mapped genome, which is to say, not nearly as interesting as we had hoped.