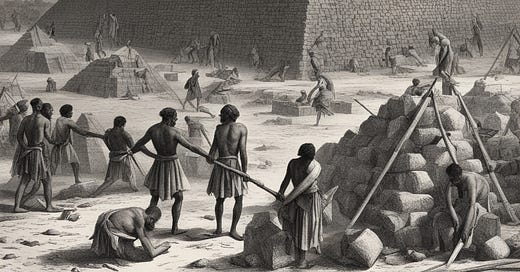

In the late 1960s, architecture critic, urban planner, and historian Lewis Mumford described the concept of a “mega machine” in his two-volume series The Myth of the Machine. Ancient Egyptians built pyramids with megamachines. The Third Reich built a megamachine intended to take over the world, and the Allied powers constructed megamachines to stop it. Megamachines can be technologically simple, but they coordinate and organize human actions to achieve large and even awe-inspiring results. Importantly, the architecture of the entire machine is largely invisible, “composed of living, but rigid, human parts.”

Megamachines, in other words, are not just machinery. They’re humans and machinery. They’re mega because of the human factor—the number of human actors involved is typically thousands, tens of thousands, or more. They’re giant scale.

Megamachines, said Mumford, are assembled to perform tasks which would be impossible without them (a few Egyptians could not make a pyramid). They characteristically glorify their designers, not the human “components” of the machine, who stand unacknowledged in the background. Importantly, there’s an element of myth or even religion attached to the megamachine. They serve the gigantic visions of their designers. They’re larger than life.

Mumford also referred to megamachines as the “Big Machine.” He adopted language when describing megamachines for specific purposes, like “labor machine,” and “military machine.” Today, Dataism and AI have transformed the web into a “data machine.”

Seeing the web through Mumford’s eyes, as a type of megamachine, has a through-the-looking-glass feel to it, in large part because nearly everyone prior to this century assumed the coming of the “new economy” meant decentralized networks of free and empowered users, not centralized schemes that hoover up the writing of people left unacknowledged. But it’s clear now that a handful of large monopolistic companies have managed to subvert that vision. The trend of the web today is toward further centralization. A data machine is a mechanism of central power and control.

ChatGPT is the latest incarnation of a data machine, a deep neural network conversational system whose designers co-opted millions of human contributions of writing on the web to train what’s known as a “large language model” of English, now GPT 4. Microsoft has invested $13 billion to date in OpenAI, the parent company of ChatGPT. The much-discussed system can’t be customized by its many users—it relies on a billion-dollar distributed computational platform comprising vast numbers of specialized chips called GPUs. What’s left out of the discussion is an inconvenient and ominous fact: the system wouldn’t work at all if not for the millions of human contributors on the web. Like data-driven AI generally, ChatGPT and other generative AI systems are parasites feeding on human production.

ChatGPT sits on a billion and now trillion parameter neural network, trained on billions of words culled from web pages and digitized books (there are about five million digitized books to date). The architecture that wraps the neural network is also a twenty-first century innovation, known as a “transformer” with “attention blocks,” that enable the system to examine the words (tokens) offered as a prompt. This attention mechanism, technically a 2017 innovation by Google Brain and Mind scholars along with researchers from Toronto, captures long-range dependencies in language and helps account for the uncanny performance of ChatGPT and other systems using transformer-based language models.

In a Hitchcockian sense, though, the success of Big Data AI projects like ChatGPT have converted the entire web—or a large portion of it—into a data machine. The human actors remain invisible (though essential), while the glory goes to Sam Altman, head of OpenAI, and his engineers, and the now typical mythology about superintelligent computing blesses the data machine as if it’s a near religious artifact, fantastically designed and deployed by the new Pharoah.

It’s true of course that ChatGPT and other data machines relying on invisible human intelligence don’t coerce the many humans unwittingly involved. But close enough. No credit or recompense is given. The Big Machine—another of Mumford’s memorable phrases—is all.

In future posts I’ll explore further Lewis Mumford’s megamachine concept and unpack generative AI systems like ChatGPT, to demystify what they do and how they do it. It’s I admit a shocking conclusion, but I think there’s a case that the new data machines of the modern web are a ricorso, a return to the past, where leaders gloried in megamachines and the myths they inspired, while disguising the actual, all-too-human dynamics of their construction and operation. We are repeating mistakes from our past, not rocketing forward like modern media, pundits, and increasingly the public believe—or want to believe.

My next post unearths another throwback: the mid-twentieth-century age of Big Iron.

Thank you, readers of Colligo.

Erik J. Larson

Aren't the large language models just mega-plagiarism machines?

Hi Keith,

Thanks for your comment. I read your blog post, and I agree with you that even language like "hallucinates" sort of obscures the machinery of what's happening (a malfunctioning brain? Really?). We do this andromorphic exercise with tech generally--ships becomes "she" somehow to Navy admirals and captains etc. But the language is sort of endearing, or it serves some pragmatic end, it's not potentially fundamentally confusing, so I think the cases are in fact different. Thanks for your comment again. It's gratifying to see folks engaging the material. My hope is that we can actually solve or help solve some of these problems one day. (Big hope.) Best, Erik