Dubious Utopia

Nick Bostrom's latest book wonders about a world where everything's solved

Yeahhh. If you could just go ahead and….

Hi everyone,

On some occasions I find that I don’t have anything burning to say. This is where Nick Bostrom comes in handy. Bostrom’s latest book, Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World is a departure from his gloomy 2014 bestseller, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. A decade ago, we were hurtling toward an apocalypse. Now, says Bostrom, we’ve got a new problem. We may get bored.

Going to Work Today? Nah.

Bostrom’s argument in Deep Utopia hinges on an oft-mentioned but entirely hypothetical worry among economists that AI and automation will reduce the need for human work until there’s nothing much left for us to do. On at least one famous reading, that was the plan. Sour and destitute in the squalor of the Industrial Revolution, Karl Marx famously asserted that in a future communist paradise sporting advanced tech, we humans would be positively bursting with options, all pretty good:

[technology]… makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd, or critic.

Marx was, of course, full of it. But his vision of future material abundance got taken up by the techno-futurists in the next century, espousing what I’ve called “Dreamy AI,” where advances in AI free us from crappy stuff and make possible technological utopias, where it’s all wonderfully pneumatic and we’re joyous and carefree, not pathetically scrambling for cover, hunted down by killer robots and SkyNet (what I’ve called “Fearsome AI”). Dreamy AI owes a lot to Marx, who saw humans as material beings and thus problems as material problems. Advancing technology, in this picture, becomes an almost spiritual force. It saves all. It liberates.

Work Sucks. So Does Not Working.

Bostrom, a tall chrome-domed Swede with training in philosophy and economics, takes up in Deep Utopia a theme that Marx handily ignored, or handily dismissed—that a technological utopia full of advanced machines doing all our work might be, well, boring. We like to do work (careful, careful). Pilots at least start out by enjoying flying. Driving a car is fun, too. I like to plant flowers. I like to hand wash dishes. I’m not a big fan of managers—or anyone telling me what to do, for that matter—but working with people to solve interesting problems can be rewarding as well. Even if such pursuits are voluntary, someone is typically better or more experienced or just more available—sort of a manager. We thrive in such “soft” hierarchies, it would seem. Indeed, much of what we do that economists call work is actually social and intellectual and physical engagement.

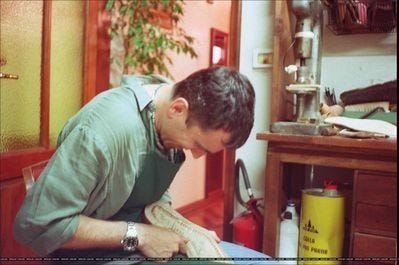

To be sure, no one in their right mind relishes the prospect of digging ditches or hauling off construction scrap in the afternoon sun (que Office Space). But manual labor of this stripe does get eliminated or improved by machines. What’s left can also be engaging and fun. Daniel Day Lewis, one of the greatest thespians and movie actors of all time, retired to learn how to be a shoemaker, apprenticed to someone who had achieved a mastery of it. Shoemaking? Why not?

Daniel Day Lewis Making Shoes

Let’s face it, the entire concept of utopia seems a little suspicious. Perpetual vacations tend to morph into something trickier, like “retirements.” People who retire when they’re retirement age—or younger—report spending psychic energy trying to figure out what to do, rather than running around in jovial freedom. I recall marketing guru Tim Ferris—of The 4-Hour Work Week fame—warning readers in almost ominous language that taking what he called “mini-retirements” would likely land you in existential angst, boredom, soul searching, and even depression. Cool. Sign me up. (Actually, no, really. Sign me up.)

Bostrom takes up this worry, wondering in his typical economic verbiage what will happen to us when technology does all the economically valuable work at near or zero-cost. He calls this a “post-scarcity” future—a future with more abundance and less work. It’s a famous trope among economists. The famous 20th century economist John Maynard Keynes once predicted that a hundred years in the future—now, basically—the work week would be 15 hours. He put his finger on a broad trend that’s actually true: in the rich world working hours have dropped from more than 60 in the late 19th century to less than 40 today. At least on paper, we are working less than our harried ancestors.

The Tom Sawyer Syndrome

I wonder, though, whether we’ve actually been bamboozled into working more—quite a bit more—than before AI and the web. I’m typically happy to answer questions posed to me by LinkedIn (seems like my opinion matters), or respond to other questions online, or offer sometimes even lengthy responses and commentary. By traditional standards I’m doing this all for free. Many of us are. (Take a moment after reading this, and pat yourself on the back for a job well-done. You helped train LLMs and AI!) In short, we’re feeding data to machines owned by other people all the time. AI is trained on human generated data, so in a sense we’re all working long hours—we’re feeding the Big Tech computers, and padding the Big Tech luminaries’ pockets. Are we really “working” less? What do you mean by work? If I’m replying to someone on social media, sure, it’s voluntary. But it gets dicier when answering prompts and questions for tech companies that take your prose and ideas as proprietary data and intellectual property. Haven’t we all been working a hell of a lot?

Ma’am. Step Away From Your Child.

Back to Bostrom. Bostrom also worries about what he calls “post-instrumentalism,” positing that AI and robotics may one day step in to take over stuff we presumably want some engagement in, like parenting. Ostensibly, he’s posing hard questions about our psychological and emotional futures, when technology has a much greater reach and sway (if that’s possible). Ostensibly, he’s worrying about boredom and meaninglessness and the human condition. But Bostrom is a techno-futurist, and akin to the concept of heaven in religions, he sees digital technology as opening up vast possibilities we can scarcely dream of—wonderful far off spaces for the mind and heart, expanded experiences made possible by computers and simulation. True, we may not get to enjoy being an actual chef anymore, or really fixing shoes, but we can hop into a simulated world using neurotechnology. We can make virtual food, and fix virtual shoes. In other words, in a post-instrumental world, where even the most human of responsibilities we’ve had are no longer, we can spin up an experience machine and get back into the groove. I’ve always found this vision not only far-fetched but distasteful, even if some version of it could come to pass. I like the natural world, and I like doing things in it. I’m pretty partial to human agency.

Over the years, economists have argued, in effect, that AI utopias aren’t plausible, not because AI will never become truly “superintelligent”—though that’s an excellent reason—but for all-too-human reasons, like the phenomenon of “positional goods.” In 1977 Fred Hirsch argued in “The Social Limits of Growth” that wealth increases don’t necessarily lead to boredom, but to a desire for more positional goods: goods that convey to their owners a high relative standing in society. “Positional goods” captures the idea that if I roll up in a $100,000 sports car and you have holes in your shoes, I win. It’s status competition, basically. Rich folks see too much abundance to make companies for profit, so they pivot to rocket-races to Mars—you lose! Keeps things interesting. Folks will take up traditional competitions with great zeal, too, like board games and sports. (Chess playing is actually more popular since Kasparov lost to IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997. Turns out, humans still like chess, even when they’re comparatively bad at it compared to AI.) Maybe an ongoing desire for positional goods is a bad thing, looked at a certain way. But the communist utopia idea seems creepier. Is the techno-utopia really well thought out?

AI Took My Job! Relax, Take This One.

So far, AI seems to create jobs, not eliminate them. We don’t have much evidence that jobs are actually disappearing, even if we are (doubtfully) working less hours. And in spite of what techno-futurists always say, AI will likely keep screwing things up, and requiring its handlers and others to do more work to keep it all moving along. I can see scenarios where large segments of the human population are spending their work weeks fixing and fussing about machines—like we do now. Invariably, a tech nerd will insist that the AIs will start fixing themselves. Common sense tells us that we’ll be even further mired in more and more complexity, doing more and more work for the technology we’ve built. Bostrom’s visions in both his earlier homage to Fearsome AI and his latest speculation about Dreamy AI each have an abstracted and hypothetical and out of step feel. For me, he has the opposite effect of the point of his books—I feel as if either Fearsome or Dreamy AI is just a silly academic game.

Here’s what we know. Compared to even two decades ago, we now have vastly more powerful digital technology and AI. But we’re plunging into global conflict with two increasingly troubling and nasty wars, spying on and surveilling and deep faking each other to the brink of instability and madness, all the while reporting record anxiety and depression. Suicides have increased as technology has marched forward. Teenage girls in particular are in big trouble. Boys, too, are dropping out of school. And we have a Fentanyl epidemic (that China seems pretty happy about). Technology doesn’t seem to be moving us toward Bostrom’s utopia. Looking around, it seems destined to keep complicating our world, fixing some stuff and breaking lots of other stuff, and often ruining us and bumming us out. Why are we so interested in what we’ll do when no one has to work and we’re free to hunt, fish, fabricate photos of the Loch Ness Monster, and argue about the value of Kandinsky? I’m not sure. It’s not a very likely future given what we know about AI.

Our Insoluble World

Bostrom. I guess someone has to say the stuff we know ain’t true. The subtitle of Deep Utopia says a lot: Life and Meaning in a Solved World. That’s the problem. The world we live in will—can—never be “solved,” like an AI program running a calculation. Humans will still throw beer cans at the T.V. (or whatever the latest gadget is) and engage in status activities and chase after positional goods. We’ll still run around hunting and fishing and trying to pretend like we’re art critics. But none of it seems like a coming utopia. Warfare the world over escalates. Power seems pretty adept—in every age—at one-upping truth. I’m not seeing a utopia in the future. I certainly don’t see an “AI utopia.” Let’s face it: there isn’t a technological solution to life. There’s only a human one.

Erik J. Larson

Colligo has the world's most thoughtful and interesting readers, no doubt. I had to blow through this post as I'm writing a proposal for a second book, and on some occasions I don't have all the notes and research and that kind of internal intensity about a post. Fortunately, I have Eric et al! Thanks for adding immeasurably to what I said. I'd like to return to this issue of utopia. All best, Erik

You make a good point when you observe that we will likely always chase positional goods, and that a "post-work" tech utopia will likely just contain redefined positional goods.

Some thoughts about the possible political-economic circumstances of a "post-work" tech utopia:

(1) Tech needn't have become absorbed into capitalistic structures, but it has. (Failing to foresee this might have misled Marx.) And this absorption won't likely be reversed.

(2) As it metastasizes, tech necessarily exudes a massive, material matrix around it. That matrix nourishes and sustains tech. It also therefore nourishes and sustains the illusion, promulgated by tech, that tech is immaterial. There will always be a need for human beings to tend to the material framework.

(3) Given 1 and 2, it's likely that the work done to maintain the material framework will most likely be work that, by its very place in our political-economic arrangement, contributes to the production of goods valued by the market (be that production via financialization, via entrepreneurialization, etc.). That is, the work will (also) be labor.

(4) Given 3, it's worth wondering whether the same old stratifications and inequalities will reassert themselves. There will be the Haves, the Front Row, playing the market or exchanging AI art out on the veranda as hovering robots buzz around them emitting a salubrious vapor of vitamins and microdoses of psychotropics. And there will be the Have-nots, the Back Row, performing labor that is accorded no dignity by the overclasses and yet is necessary for the overclasses to do the things they tell themselves make them more important.