The Left Brain Delusion

A trove of evidence suggests the hemispheres of our brains see the world differently. The side that's winning is the one we need less of.

Hi all,

This post is in two very identifiable parts. The first covers the neuroscience of laterality research and what it might mean for us today. The second is my account of grooving. This post is for everyone out there who wonders about this stuff. Let’s wonder together.

Steamrolling Human Agency

Techno-futurists love to dream up visions of the future. Invariably, these are worlds where everything is under control—where every problem has a solution, and the future unfolds exactly as planned. We do seem to be moving toward some sort of centralized loss of agency, but what’s distinctive about the techno-futurist vision is the belief that this is not only inevitable but wonderful. Self-driving cars eliminate wasted time in traffic; smart cities like Songdo or Masdar City adjust every streetlight and service in real-time to optimize efficiency. AI-driven healthcare, like the tools developed by Google’s DeepMind, promises pinpoint diagnoses, while automated finance uses algorithms to manage our money and secure our futures. Everything works, all the time.

Doomsday worries seem light years away from this alacrity, but in fact, they reproduce the same confident vision of a techno-future—just flip the coin to "everything is terrible." Skynet awaits, The Terminator is knocking, and the machines are destined to rise. It’s the same weirdly confident vision of a future controlled by technology, just in a darker shade. The message is delivered with supreme confidence and self-righteous certainty, as if spoken by Moses delivering the Ten Commandments. There’s something delusional here, yet it’s almost a mainstream game, especially with our recent immersion in deep learning and Generative AI.

But here’s what’s unsettling: this vision doesn’t just overlook human agency—it steamrolls it. Where does this unshakeable confidence come from? Are these "tech bros" genuinely cynical, or is there something deeper at play—a kind of delusion?

Recent neuroscience has added substantial weight to our understanding of how the brain’s hemispheres operate. While the old pop psychology myth of "left brain-right brain" has been thoroughly debunked—no, your creativity isn’t limited to one hemisphere—what’s fascinating is that modern science confirms something just as compelling: the two hemispheres of our brain really do see the world differently.

Disney’s Nemo

Such a stark asymmetry seems inefficient at first blush, but it’s not. Fish, for example, show a clear division of labor between the hemispheres—one side of the brain keeps a lookout for predators, scanning the environment for threats, while the other focuses on finding prey, zeroing in on the specifics. Astoundingly, the lowly C. elegans—sporting just 302 neurons—shows left-right valence. Nematodes, in other words, would have brain hemispheres if they could but only evolve more complexity. All of this tells us something rather shocking: there’s some very deep reason we have brain hemispheres, and by obvious implication, there’s likely some very good reason that they see the world differently.

Keep it simple, stupid. The C. Elegans

The astonishing, quite scientific hypothesis here is that our tech-dominated society is skewed toward the "confident categorizing" emblematic of left-brain dominance. We seem to be recreating the world—nature itself—in an image suitable for manipulation and grasping. And the psychology behind this is just as unsettling. The left brain is a superb confabulator. Take, for example, patients with right hemisphere lesions, as studied by neuroscientists like Michael Gazzaniga. These patients often experience something called "anosognosia," where they are completely unaware of their own paralysis. Here’s an example:

Doctor: "Can you move your left arm?"

Patient: "Yes, of course."

Doctor: "Could you show me?"

(The patient doesn’t move their arm.)

Doctor: "It looks like your arm didn’t move."

Patient: "Oh, it’s just a little tired. I’ll move it later."

Doctor: "Are you sure you can move it?"

Patient: "Yes, I just don’t feel like it right now."

The left brain, in its attempt to maintain its confident narrative, will invent elaborate explanations for why their immobile arm is just fine—perhaps it’s someone else’s arm, or maybe it’s just resting. The point is, it will lie to maintain its sense of control.

This tendency to confabulate, to confidently assert control even when the reality is far more complex or uncertain, is deeply embedded in the left-brain way of thinking. And it’s this very mindset that might be driving our increasingly technocratic, hyper-controlled vision of the future.

The Road Ahead: Straight, Obvious, and All About Control

“The world is probably round," said Vincent van Gogh. But left-brain dominance wants it to be rectilinear, like the precise grids of Haussmann’s Paris or the rigid structures of early factory towns. We see this way of looking at reality starkly emerge at the outset of the Industrial Revolution, in places like Manchester and Birmingham, where suddenly the grasping and manipulating, the confident push into the future, overwhelmed the right brain’s feeling for music, prosody, the Gestalt.

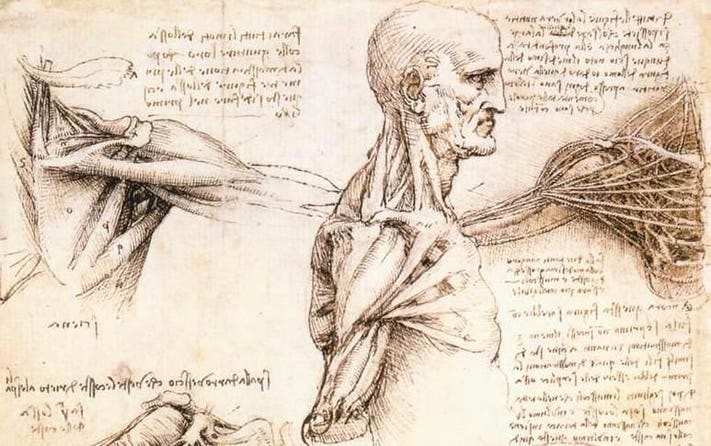

A machine is broken down into parts. A Gestalt can’t be understood in parts at all. This vision of our future, appearing around 1800 in Western Europe and quickly spreading to the U.S. and the rest of the world, was apparently irresistible and implacable. Oxford University’s Iain McGilchrist traces our left-brain craziness back to Enlightenment thinkers like René Descartes, who famously likened nature to a clock, its parts ticking away in perfect, predictable order. The "roundness" of nature dominated the big visions of human excellence we saw flowering in the Italian Renaissance and the great eras of human potential in the classical age of Greece and Rome. The European Renaissance, exemplified by artists like Leonardo da Vinci, obsessed with revivifying the classical era, where figures like Petrarch saw progress as more than linear progression but also as reaching back into the past. Continuity. Perspective. The whole, not the parts.

DaVinci’s The Last Supper

So, are we children of the great left-brained delusion, whose most recent adherents are our indomitable tech luminaries? If so, what comes next?

*****************************

If you have to ask, you’ll never know. - Miles Davis

Groove, Beotch.

I bought an old spinet piano a couple of years ago and plopped it down in my living room, where it dutifully collected dust until about a month ago, when I started playing. I found a charming retired professional musician who was willing to take me on as a student after a multiple decade hiatus, in fact. The instructor was necessary, as I quickly discovered I had lost the ability to read sheet music and quickly ran out of steam trying to pick up songs I once played from memory from my old piano books. I had to start over, somewhat like a patient with brain damage, as the “catastrophic forgetting” was comprehensive—my brain simply didn’t “get it” at first. The rest of the story is more fun.

I picked up the groove (and that’s what it is, a groove, and I’m talking here about playing classical stuff from Bach, Mozart, Beethoven et al) after playing a few scales and sitting with my instructor in her studio in College Station, Texas. In fact, the story now gets positively delightful, as after about thirty minutes at the piano playing simple scales we switched to songs, and Charlotte was soon telling me that “I’d picked up two weeks of lessons in twenty minutes.” Let’s not roll out the bunting just yet. I used to play. Back to the brain.

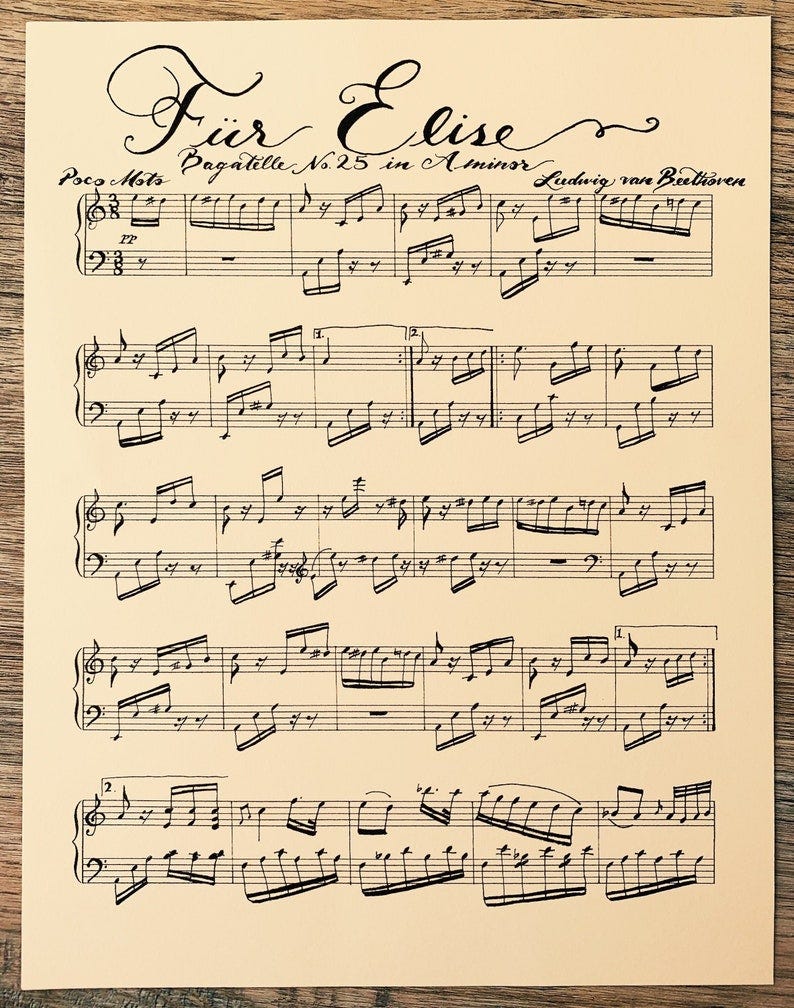

Your left brain unpacks music in roughly the same way it looks at computer code, natural languages like English or French, and I suppose stereo instructions. It breaks down the song into its constituent parts—left hand playing Bass Clef and right hand playing Treble Clef—and understands the song in terms of the spatial distribution of notes of varying lengths (symbols) on the staff. That’s the part I had forgot; I couldn’t make heads or tails of the nuts and bolts of the sheet music, and so at first, I couldn’t play.

Doh! A song I used to play…. and had catastrophically forgotten.

But what makes music so powerful and cool is that we don’t stop with the logical reductions of the left brain. Once we’ve unpacked the music in symbolic form, another just beautiful cognitive step happens, as any musician will recognize. The right brain “sees” the whole thing as one piece. The groove is just the state of flow in your brain when all that detail no longer matters and you quite literally feel the music flow through your fingers and the rest of your body, your embodied cognition, as it were. At some point—again as any musician knows—you’re looking at the same symbols but because you see the entire thing, the Gestalt, you somehow know where the notes fall without this laborious unpacking process. Then you’re playing. The “making it seem easy” aspect is what musicians do, and how easily you can make it seem to play the most ridiculously convoluted and complicated pieces is roughly how good you are—the easier it seems and feels, the more you’re grooving.

This person is grooving.

In neuroscientific terms, here’s what’s happening when you’re grooving: your right hemisphere looks at the sheet music and says “Oh, this is a job for the left hemisphere,” and passes it over. The left brain then eagerly unpacks it, analyzing it in its trademark linear sequential fashion, and re-presents it, back to the right, which (if you’re a player) sees the whole thing, now properly analyzed. The groove is happening over in the right part of your brain, which is now magically traversing all this complexity from the left hemisphere.

If you have to ask…

Back to the pressing question of our left brain delusion. The question I raised above in this piece can be summed as, how do we make more of our world be like the integrated experience of grooving in the right hemisphere, rather than the manipulative categorizing and reducing and picking everything apart from the left? You might rephrase my question this way: how does life have a groove? And one thing I’m damned worried about is that there’s so much technology in our lives now that we’re stuck over in the confabulating, supremely confident non-groovy grasping and manipulating and screwing up the world place, where everyone thinks everything is just obvious, and there are no big mysteries left and no big questions to ask, and the future doesn’t need us. I’m worried that we’re re-making and re-presenting the world in our image at a time when increasingly we can’t see the forest for the trees. And now we’ve got quite a task in front of us. Where’s your groove?

Erik J. Larson

The thing is the forest is still there, whether you can see it or not, and will defy every effort made to reduce it to a mere collection of objects. There is no tech dystopia or utopia coming, only the consequences of attempting to make one: a devastating lesson in the impossibility of micromanaging fractal complexity.

To be a little less vague both the tech cultists and the doomsayers accept the fundamental technocratic premise that we understand a lot more than we actually do, and are in control of a lot more than we are. All evidence points to the contrary: that every single grand technocratic project has failed catastrophically; every single time they thought they had it all figured out; and it's vanishingly unlikely that they've got it all figured out this time, given results of all past experiments.

Imagine instead a future where this premise is fundamentally incorrect, and the relentless undermining of every known-good state of every aspect of society will lead not to its New and Improved (tm) replacement, but collapse and regression to an earlier, lower-"progress", less complex, fragile, and interdependent state of being. That's where we're going. And after a period of adjustment, it's going to be pretty nice.

The whole notion that we will end up with either a technologically controlled utopia, or some kind of panopticon AI-supervised dystopia, but either way with the machines in charge, is depressing, but also boring, and highly unlikely. Machinery never works as well as people think. Vendors, overhype what their gear can do, people fail to follow the manual and break things, upgrades are installed that actually make things worse, etc. People still need to make it all go, which means it will never be perfect, neither perfectly good, nor perfectly awful.

One science fiction writer who understood this was Philip K. Dick. In his novel The Penultimate Truth, there is a supposedly fully automated underground civilization, living in big cylinders. But we find out that there’s one old guy who is the only person who knows how to keep the machinery going, and he is plugging things and keeping it working, but if he died, it would all stop. So the protagonist, when he finds out the old guy is dying, violates all the protocols, and comes to the surface to get a prosthetic pancreas, and he finds out that everything he was told and that he believed wasn’t true. But the image of a futuristic world that is only kept going by some guy, down in the basement, with a greasy workbench, and old tools, and tape, and spare parts pulled off of stuff that’s not being used anymore, that is how any future world, any world reliant on technology, will always have to work. Even chief engineer, Scott on the Starship Enterprise in the original series worked like this.

So if the Utopia and the dystopia are not going to happen, what will? More ordinary human muddling through, that’s what will happen. Some of it will be great, some of it will be destructive, but hopefully the net direction, the sum of all vectors, will be positive.