Dataism is Junk Science

Dataism isn't a new religion. It's just an old debunked theory of science.

I’ve been thinking lately about the disappearance of classically debated ideas in the 21st century. Once upon a time fierce debates raged on in classrooms and conferences and around campfires about whether God existed or if scientific materialism were true. “Mechanism” challenged earlier notions championing the uniqueness of human minds, a view sometimes called “Mentalism.” Cartesian Dualists insisted on two substances—mind and matter—while Property Dualists haggled endlessly about whether mind was not substantial but merely an emergent property. The philosopher of mind David Chalmers memorably distinguished between “hard” and “easy” problems in neuroscience, the former referring to problems taking consciousness or mind seriously, the latter concerned only with the “functions and structures” of science—neurons and action potentials and all the rest.

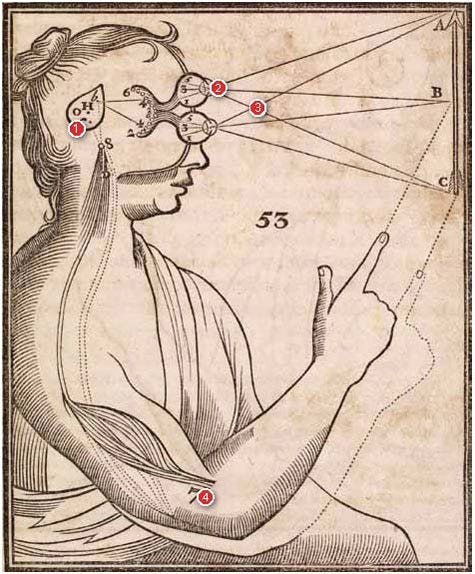

Descartes’s famous depiction of his first date. (I jest.)

This is the philosophical world I came of age in. It’s now, as far as I can tell, mostly gone. The significance of this is hard to overstate, and it’s all the more troubling because far from overstating it, no one seems to state it at all. Welcome to the 21st century: the fetid jumble of digital consumerism and shallow worthless philosophy. The universe is a big computer, we’re told, and data is not only the new “oil,” but the new religion.

If the 20th century was an impossible stalemate among well-defined competing ideas, the 21st century is an impossible confusion among fuzzy and poorly developed ones.1 It’s no wonder the world seems too often an anxious befuddled mess, full of power relationships and contempt for truth. Increasingly, it is.

Enter Dataism, a term innocently introduced by New York Times writer David Brooks in 2013:

If you asked me to describe the rising philosophy of the day, I’d say it is data-ism. We now have the ability to gather huge amounts of data. This ability seems to carry with it certain cultural assumptions — that everything that can be measured should be measured; that data is a transparent and reliable lens that allows us to filter out emotionalism and ideology; that data will help us do remarkable things — like foretell the future.

Brooks saw early on that something was fishy with our philosophy and our self-image in the new hightech century. In a telling inversion of Horatio’s admonishment that there’s more than dreamt of in our philosophy, Brooks fingered what’s become an all out crisis today, that there’s decidedly less. What underwrites “dataism” isn’t additional insights into nature and man but a lazy and self-serving rejection of big-picture insights or ideas at all. All those big ideas we used to argue about are now boring and mostly forgotten.

The smug self-aggrandizing ethos of this century is born out in troubling trends, like a decline in religion (meaning Christianity, of course, not Islam), which hovered at 70% for decades and then cratered to 47% by 2020. (What would Heaven be in a data-driven world, anyway? Really big data? What would Hell be? No data? Argh.) Add to this the more recent depredations of science. Last November the Pew Research Center devoted an entire report to our declining trust in science and scientists:

As trust in scientists has fallen, distrust has grown: Roughly a quarter of Americans (27%) now say they have not too much or no confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests, up from 12% in April 2020.

Seems like, increasingly, we don’t believe in anything. That’s nihilism, of course (cue Sartre). But I don’t think our problem today really is nihilism. That would be something to reinvigorate the old debates. We could exhume the gloomy French existentialists hiding in Vichy France or, after the Great War and the Second Great War and the bomb, insisting nothing anymore could matter, but we should keep going anyway. Camus could pitch in with novels about absurdism.

Sounds like a hoot, but it’s not our problem. We believe in stuff. It’s just stupid stuff.

Back to Dataism. Dataism is actually an old idea regurgitated in the modern era to capitalize on the hype around what started as “Big Data.” This term—big data—peaked in popularity in the late 2000s and early 2010s, and captured the idea that orders of magnitude more rows in your spreadsheet (or .csv file) meant greater performance scores on a range of tasks in AI, or more accurately, machine learning. Big data meant more disambiguated words—no, not the financial institution, I mean by “bank” the ground next to a river—more and better personalized content, more accurate product recommendations, news articles correctly tagged by topic, image recognition, autonomous navigation, and all the rest. Big Data made machine learning work so well in the late 2000s that Chris Anderson, editor in chief of Wired Magazine until 2012, declared in 2008 that science—scientific theory—was dead, and big data had killed it. (Anderson later recanted. The point was made.) In short, big data powered the web, your smartphone, the AI algorithms, and seemingly everything else. How could data not be a religion? Dataism was a fait accompli.

The popular historian Yuval Harari picked up where Brooks’s sober and cautionary analysis left off: “data-ism” was now “Dataism.” Dataism expresses the view that information flow is of ultimate value, both in the world of bits and the world of atoms. In his 2016 manifesto, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harari’s pen practically caught on fire:

Dataism declares that the universe consists of data flows, and the value of any phenomenon or entity is determined by its contribution to data processing.

… we may interpret the entire human species as a single data processing system, with individual humans serving as its chips.

We may. We shouldn’t.

More recently, in 2022 the Hungarian physicist Albert-László Barabási, best known for his 2002 Linked: The New Science of Networks (notice how “science” is still in the hunt), cranked the needle to eleven:

Whether we consciously recognize it or not, data creates the imprint of the universe in our collective consciousness. In this moment of collective migration into digital and virtual realms, data has become, in a very tangible sense, our new reality.

I respect Barabasi’s earlier foray into network science—it was pop science, but at least it he was trying to take science seriously—but I find his latest enthusiasm a bit hard to swallow, to put it mildly. It smacks of the same confused jabberwocky that dominates more and more of our online experience, with its new menu of experts, doomsday prophets, conspiracy theorists, techno-futurists, and know-it-alls. Sure, the 1970s gave us New Age thought. But that was relatively mild and touchy feely and decidedly not part of our technological world. To reject New Age thought, just get up and leave the Esalen Institute. Peel out of Big Sur. Throw out the incense. Lose the Tie Dye. Grow up. To reject Dataism, contact Elon Musk about a ticket to another planet—and good luck. Dataism is dangerous because, let’s face it, it’s woven into the very fabric of what we do and experience as real everyday.

Thankfully, while we’re awash in data and data analysis, we have no good reason to accept a new religion called “Dataism.” Turns out, it’s just good old fashioned junk science.

I’m hearkening back to an old piece I wrote for a now defunct publication called Inference: The International Review of Science, that once counted Noam Chomsky on its board and was based in Paris, France (last October, I visited the former editor in chief at his apartment in Paris, with a thrilling view of the Seine. I wish it was still operating, and that I could spend some time writing in Paris). The piece was titled “Big Neuroscience” and came out in 2015. At the time, “Big Data” was still a buzzword and big science projects like former president Obama’s BRAIN Initiative and Europe’s even grander and more hopeless Human Brain Project were in the news. The spreading cancer of “Dataism” was already evident: the projects were exorbitantly expensive and, especially in the European case, quite hare brained and ill-thought out. Still, they managed stupefyingly confident proclamations about the future of neuroscience, and the coming of a thinking computational replica of the human brain.

None of this even remotely happened, of course, as I’ve written about before (it’s in the Myth, for instance). The US wisely confined its rhetoric and research to more reachable goals like better cures for Alzheimer’s and other brain-related diseases. The EU went in whole hog.

Even then, in the mid-2010s, one could read the tea leaves and see that science was soon to become whatever a supercomputer cluster said it was. The editor and I discussed it, then argued about it, then the clouds parted and I realized we were talking about a naive empiricism again. That idea had been roundly defeated decades ago. That idea, no serious philosopher of science could believe anymore. That idea was Dataism.

I’ll have to recapitulate the argument from memory (the piece is no longer available online), but in sketch it’s simple enough. Empiricists like J.S. Mill in philosophy and Earnest Mach in physics rejected speculation and theorizing (so the story goes) in favor of gaining scientific knowledge by simple observation. The view culminated, with various revisions, in the famous Vienna Circle. Its (also famous) members championed a view known as “logical positivism.” Logical positivism and the empiricism that undergirded it failed, ignominiously, as it had not only internal logical problems (it was, essentially, self-defeating by its own definition), but also was an inadequate explanation of how science advances and what actual scientists do. My example, as I recall, involved making observations of stuff that floats—or doesn’t—in water: wood and iron, say. Empiricism would have us observe lots and lots of instances of something floating and then inscribing in one’s notebook “Wood floats” and “Iron does not,” under such and such conditions.

This is a stage in scientific discovery and even an important one, but it’s clearly not the whole of it. The problem with this type of “big data” analysis is that it’s relatively moronic to keep dropping pieces of wood in a pond trying to understand whether it floats (it has a “floating virtue,” the Scholastics might have said, to make a bad joke). There’s a simple formula you want to arrive at, which of course is motivated and had to have been discovered by prior observation: average density:

We can use 𝜌 = 𝑀/𝑉 , where 𝑀 is the mass of the whole object and 𝑉 is the volume of the whole object, to find the average density of the whole object.

Yes we can use that formula. And yes we should. Now, instead of chucking lots of pieces of wood into a body of water and trying to home in on what floats and what doesn’t, we can apply this formula. That’s how science works. Our latest Dataism advocates want to keep us trapped in the old dumb ideas of eyeballing lots of pieces of wood in water—writing them down as “data”—and then feeding all this to a computer to determine what’s real. This is a retrograde epistemology that’s been thoroughly debunked, and only recently has reemerged with a new breed of enthusiasts who seem not to notice that they’re trafficking in defunct ideas—and pushing them on an increasingly ill-educated and confused public.

Dataism is bullshit. Data is what we use to maintain bureaucracies and keep track of fitness goals and sales and prisoners and investments. It’s central to science, as it’s the raw material in the form of measurements, in diverse scientific fields (where would astronomy be without data?—true). But data and its analysis is just the input to the human mind, where thought and insight occur. We use data instrumentally and not as a final cause, a worldview, but as a means to theory and ideas. Data isn’t absent science and discovery, it’s just a part. Our latest reductionism is another dead end in the history of thought, and it threatens to rob us of a fully integrated picture of ourselves and the world we inhabit.

We’re capable of more than acting as conduits for consumer electronics ideas and the “thought leaders” getting rich pushing them. Are we? Yeah, we are. Let’s start showing them.

Update: A reader, Jonathan Bisson, found the “Big Neuroscience” piece and sent it to me on LinkedIn. I’ll leave the post as is. Here’s the article. Thanks, Jonathan!

Erik J. Larson

I’m aware of the spread of tribalism and the problem of identity politics hijacking much of the Academy. It’s outside scope for this post, but I may say something about it later. One problem I have delving into such super fun facets of our 21st century life is that, by and large, everyone is already talking about it, and it’s entirely unclear I have something novel to say. If I connect that unfortunate movement with my other ideas and views in a way that adds something new, I will indeed broach that issue.

Hi Martin,

As I sit here waiting on my Jeep to get inspected ... endless economic growth yes I really understand this pain point. I've spent embarrassing amounts of time trying to come to terms with the fact that we can't stop consumerism "once it starts." People simply don't give up the latest "innovations," barring I suppose the Unabomber. The "entrepreneurs" in this narrower and quite troubling sense are simply responding to demand--or creating it, but the difference is increasingly beside the point. I don't know what to say about this--we have eight billion people on the planet largely because we can feed orders of magnitude more people per acre. Some small percentage after benefitting economically from the very society they despise can f-off to Alaska or what have you (count me in). But the vast majority need their cell phones for their bosses and their day to day. No one is REALLY eschewing technology, anymore than no hunter gatherer insisted fire was the devil and he'd eat his Musk Ox raw, thank you very much. Complaining about tech and consumerism is a full time sport. Changing anything is a fiction novel. Argh I feel your pain. Really. It's very very difficult anymore to opt out or to change let's call it rampant consumerism and Wall Street values. I have friends who tell me they're moving to Idaho and two weeks later tell me they got their investment and are opening offices in Seattle. No one is--really can be anymore--truly serious about opting out. I have European friends who are energetically confronting the "American experiment"... using Silicon Valley technology. I don't blame them and am somewhat of a Europhile myself, but it again highlights the fundamental Sysophysian challenge. Perhaps it's a harbinger of the end of times, and THIS is the exact problem I want to discuss, so thank you. I might add: I wrote a book for Harvard and now turn to saying what I say here. And it's better. Harvard is part of the problem, though I very much respect my ex editor(s). It's all hands on deck. Erik

Dataism's metaphysics envisions data as given and envisions givenness as the mark of the objectively real. Something given, it is thought, is something whose existence and character no mind, no will, could alter. And something thusly unalterable, it is thought, is something objectively real.

Brooks was on to something: with data, dataists assume they have a window onto untouched, mind- and will-independent reality.

Which suggests that dataists don't understand what data are and what makes data possible, don't understand what measurement is and what makes it possible, and don't understand observation and what makes it possible.

Thanks for another thought-provoking post!